Teaching

Just do it… Aoraki Polytechnic creative writing tutor, Diane Brown, says the only way to start your work is to go in blind without a compass, and hope you come out the other side again

Jotting down notes in a cafe penning your piece de resistance on a sun-drenched veranda; reading passages from your new novel to a room of adoring fans; walking up the red carpet at the premiere of your first film, adaptation… Ah yes, ’tis the romantic, ever-glamorous life of the novelist.

But very rarely does this all too–common literary fantasty actually become literal. In fact, Diane Brown, who has been coordinator and tutor of (Creative Writing at Aoraki Polytechnic Dunedin campus for the past nine years) says only 1% of unsolicited manuscripts sent to publishing companies by optimistic authors are actually accepted

Despite this rather depressing statistical reality check, the simple joy of words on a page will always continue to capture imagination, both of readers and writers. So where exactly should these fledging scribes start and how can they improve their chances?

To morph from an occasionally active wordsmith into a commercially viable wordmonger obviously requires a degree of natural ability. “But to write fiction”, she says, “existing skills need to be honed and new skills–like point of view (show don’t tell is important) character construction, and understanding the basic structure of novels or short stories–need to be learned”.

Also crucial–and often lacking–is “having something to say”, which in a time when a lot of it has already been said, has become even more difficult and is summed up in a joke relayed by Brown: “So, what do you do?” asked the writer. “I’m writing a novel”, came the reply, “Oh, neither am I”, the writer responded.

“Where most fall down”, she says, “is by moving too quickly”. She mentions the “10 year apprenticeship” authors should undertake before being published, and says that if you start writing a novel without knowing what you’re doing, it is likely to “just meander all over the place”.

“You have to be able to perceive it as a whole”. “It’s all about the tortoise, not the hare”. “It’s that old thing: 5% inspiration, 95% perspiration”, she says. “Although the industry is ‘always looking’ for someone who breaks the rules and turns out a brilliant piece of writing”, she says, “this level of inherent talent is rare”. Instead, “the way you learn how to write a novel is to read, and that’s hugely important”.

“I ask [applicants] if they read and if they say ‘well, I don’t read’, I can generally say they’re not going to do very well on the course”, she says. “It’s like trying to be an All Black without knowing the game. You have to be devoted to reading and have an idea about how to construct your novel”.

Learning these various techniques and formulas, she says, is much easier now than in the past, because, with numerous creative writing course, independent manuscript assessors (“who read your novel, tell you what’s wrong with it and how to fix it”), or even mentor programmes like that offered by the Society of Authors, there is much more assistance available to novelists these days.

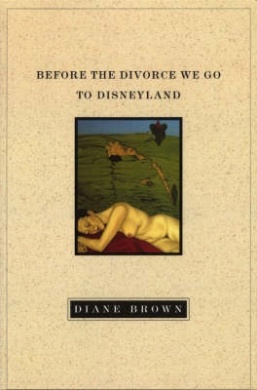

Brown, whose first book, Before the Divorce We Go To Disneyland, was published in 1997, admits, “the market may be a little over-saturated” as a result of this formalisation. “On the other hand”, she says,”it has also given plenty of writers the opportunity to improve their skills to a point where publication is a realistic goal”.

Brown, whose first book, Before the Divorce We Go To Disneyland, was published in 1997, admits, “the market may be a little over-saturated” as a result of this formalisation. “On the other hand”, she says,”it has also given plenty of writers the opportunity to improve their skills to a point where publication is a realistic goal”.

But for every successful writer who comes out of the woodwork, there are plenty more deluded souls with a rather inflated opinion of their own lyricism. “I think people believe it’s a glamorous life for a start, and because most people can read and write, they say ‘well, I can do that’, whereas they wouldn’t be so sure about doing a painting”, she says. “They have a clear idea of what they can and can’t do when it comes to that”.

“One of the biggest misconceptions about writing”, she says, “is the belief that you sit down and brilliance streams out on to the page”. “Jack Kerouac notwithstanding”, she says, “constant rewriting and revising is the major difference between those who are published by reputable companies, and those whose manuscripts are tossed on the ‘slush pile’, given a quick glance and promptly sent bin-ward”.

“The people who make it are the people who are prepared to work at it and work at it”, she says. “With some writers often spending years researching and refining their material, without knowing if the time and effort will ever pay off”, she says, “the ability to delay gratification is a very important character trait among authors. So, too, is self-discipline, a healthy sense of self-doubt, and a good bullshit detector that can be applied to your own work”. “But even if you have been published before”, she says, “very few are ever asked to write fiction”. “The only way in is to do it,” she says. “… If you’re going to be a writer, you have to be prepared to go into the first one blind, without a compass, without knowing where you’re going, and hope you come out the other side again. It’s a scary thing to do… I don’t know any writer that doesn’t have a degree of fear, but if that’s going to put them off, then they’re not up to the job”. So, does it take a certain “type” to successfully wield the quill? Brown says she has taught all kinds on her course, “but, in saying that, most writers are a bit introspective. They’re usually quite comfortable spending a lot of time with themselves”.

“You have to love writing for its own sake. You just do it because you’ve got a passion for it. You should start from that level, rather than thinking you’re going to publish a book, sell a million copies, and become rich and famous. If that’s your goal, then it’s most unlikely that you’ll ever get there. There aren’t too many J.K. Rowlings around”.

But whether attempting to gain leather-bound greatness with–a bona fide writing career, or simply to satisfy a few long-held, selfish desires and leave a little literary legacy for the family to remember you by, writing can be an exceptionally rewarding vocation. And it can be undertaken for reasons.

“[If you don’t get published], all you’re going to do is waste time. But I tell my students not to think about publishing as the be-all and end-all. Through the process of writing, you learn so much about yourself, she says. “. . .There’s a great deal of satisfaction in producing something physical. It’s just convincing other people to read it, that’s the problem”.

“Sending in a manuscript is basically like applying for a job and to state the obvious, the main goal of the exercise is to have the text-read in its entirety, rather than being rejected after seeing the errors on the first page”.

“If it’s unedited, filled with bad grammar and spelling mistakes, it isn’t very encouraging to the publisher”, Brown says. She suggests using a large font with double-spaced text on A4 paper, placing the name and page number at the top, and most importantly, checking the publisher’s website or back catalogue to ensure your book falls within their subject range. In no more than half a page, provide a summation about your target readership, who and why people will buy this book, and if you have any writing experience. She says different kinds of writing are basically separate art forms and thus require different skills. Some of the journalists she has taught, for example, never have any trouble with writing, but often struggle with character creation, and whereas fiction is usually based on the quality of the finished product, nonfiction is often signed up on the strength of the concept.

“It’s not a good idea to write a non-fiction book if you don’t have any idea where it’s going to be published”, she says. Her “very strong” advice to writers is not to self-publish novels. “But electronic publishing”, she says, “isn’t a bad option”. Try to steer clear of having your manuscripts critiqued by biased — and generally ill-informed — family or friends. Leave the constructive comments to someone with an educated, independent eye. “That’s what you see in people who are self-published: they aren’t very objective”, she says.

Review by Ben Fahy, Otago Daily Times, October 6 2006, updated September 2011